Aeschylus: Aeschylus:

when to emend

and when not to emend

di Alex Garvie, University of Glasgow

I have recently been reading with great interest the

volume of the Proceedings of a Conference held in this

University and at Rovereto in 1999 to mark the centenary of the birth of

Mario Untersteiner. Some of the papers delivered at that Conference

dealt sympathetically with Untersteiner's conservatism as a textual critic

of Aeschylus, and I have a great deal of sympathy for that myself, as I

have always considered myself to be at least moderately conservative when

it comes to textual criticism.

I have recently been reading with great interest the

volume of the Proceedings of a Conference held in this

University and at Rovereto in 1999 to mark the centenary of the birth of

Mario Untersteiner. Some of the papers delivered at that Conference

dealt sympathetically with Untersteiner's conservatism as a textual critic

of Aeschylus, and I have a great deal of sympathy for that myself, as I

have always considered myself to be at least moderately conservative when

it comes to textual criticism.

In his Repertory of conjectures on

Aeschylus (p. 3) Roger Dawe estimated that between Wecklein's

Appendix and the publication of his own book in 1965 some 20,000 conjectures

had been published, of which only 0.1% might be thought `to have hit the truth'.

Since 1965 emendation has continued unabated, and there is no good

reason to suppose that the proportion of successful, or at least

generally accepted, conjectures has grown any higher. We can all name critics

who emended a text simply because they were clever enough to think of

what seemed to them to be an improvement.

|

|

Sopra: lo studioso roveretano

Mario Untersteiner

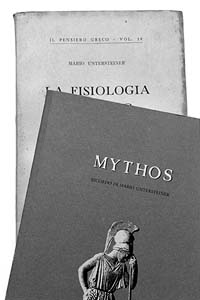

Sotto: i volumi: La fisiologia

del mito di Mario Untersteiner

pubblicato dai fratelli Bocca,

Milano, nel 1946;

Mithos, Ricordo di Mario Untersteiner,

pubblicato nel supplemento

n. 1/1991 di Materiali di lavoro

|

|

|

|

Alex F. Garvie è stato Professor of Classics all'Università di Glasgow. Allievo

del grande ellenista Denis L. Page, è autore tra l'altro di

importanti lavori sul teatro greco, come un saggio sulle

Supplici di Eschilo (Cambridge 1969), commenti alle

Coefore di Eschilo (Oxford 1986) e all'Aiace

di Sofocle (Warminster 1998).

|

|

In a very few cases these improvements may really be improvements,

and Aeschylus, if he has access to modern editions of his plays in the Isles of

the Blest, may well be regretting that he did not think of them himself. I

agree entirely with Angelo Casanova and Vittorio Citti, that the

difficulties experienced by scholars often derive from their failure to recognise

that modern sensibility may be alien to that of a fifth-century B.C. poet, that the

logic of poetry, and especially of Aeschylus, may be different from that of

rational prose discourse, and that the richness of Aeschylus' imagery and the

density of his language are not to be smoothed out by attempts at simplification

and normalisation. There should be no doubt that Aeschylus

is a difficult writer, and it is clear from

Frogs of Aristofanes that he was already seen to be so at

least by the end of the fifth century. We do him no service by trying to eliminate

all of the difficulties in his text. It is

therefore tempting to rely upon our manuscripts when there is consensus among

them, although, of course, when they disagree, choices have to be made.

It is here, however, that my worries arise. Anyone who considers the

numerous occasions in the Byzantine triad on which the Mediceus gives an

inferior reading to other manuscripts will feel that in

Supplices and Choephori, where it is the only manuscript, it is unlikely

to be a reliable guide. But in the other plays too, where there is

manuscript disagreement, there is no logical

reason why any of them must have preserved the truth.

They may all represent attempts to make sense of a deep-seated

corruption. And even a consensus among the manuscripts does not necessarily mean

that they preserve the truth. The whole tradition may still be corrupt. Of

course our starting-point must be the manuscript tradition, but

we sometimes, I think, forget that our primary duty as textual critics is not

to make sense of it at all costs, but to determine

what Aeschylus in fact wrote.

|

|

|

Il convegno Ecdotica ed esigesi eschilea,

Trento, 5-7 ottobre 2000

|

Often it will be impossible to do

this with any certainty, but that does not set us

free from the obligation to attempt it. I see no

point, then, in denying that, while it is true that Aeschylus is

a difficult writer, at the same time his text is highly corrupt.

To some extent the latter is a consequence of the former. It

is often the difficulties that have led to the corruption.

|

| Si ricorda che di recente è stato pubblicato, sulla Rivista di Storia della Filosofia n.2, 2000, un interessante articolo sullo studioso roveretano a cura di Livio Sichirollo, intitolato Per Mario Untersteiner. |

|

In his interesting Commentary on the parodos of

Choephori, first published in the 1999

Centenary volume, Untersteiner himself remarks (p. 421) of the very

difficult epode (75-83) that in his opinion one

must (my italics) follow substantially the manuscript text with only one

or two minor modifications.

In my own Commentary on 78-81 I remarked that `some sort of sense

can be extracted' from M's text, but went on to argue that that sense

was unsatisfactory and the language excessively strained. Many of us,

and I include myself, have found ourselves writing something like

'emendation here is unnecessary'.

We should ask ourselves what we mean by this. If we are saying

not only that the transmitted text makes sense, but also that it makes the

best sense in its context and that of the play as a whole, that it is in

accordance with everything that we know Aeschylus' style, and so is

probably what Aeschylus wrote, then we are justified in saying it. If, however,

we mean that because it is the transmitted text it is

ipso facto preferable to a conjecture that makes better

sense, we are on much shakier ground. We should ask ourselves what we mean by this. If we are saying

not only that the transmitted text makes sense, but also that it makes the

best sense in its context and that of the play as a whole, that it is in

accordance with everything that we know Aeschylus' style, and so is

probably what Aeschylus wrote, then we are justified in saying it. If, however,

we mean that because it is the transmitted text it is

ipso facto preferable to a conjecture that makes better

sense, we are on much shakier ground.

The question that we should be asking is not `how can we save

the manuscript reading, but how hard should we try?'

Nor is it safe to assume that corruption is always

clearly betrayed by a text that makes no, or inadequate, sense, or is simply

written in bad Greek.

Many, perhaps not all, copyists were perfectly capable of writing

respectable Greek and could scan at least iambic

trimeters. They wrote what, in most cases, seemed to them to make

sense, but that does not necessarily mean that it was the sense which

Aeschylus intended. For all we know, there may be lines in our texts which have

never been suspected, but which are nevertheless corrupt.

|

Aeschylus:

Aeschylus:

We should ask ourselves what we mean by this. If we are saying

not only that the transmitted text makes sense, but also that it makes the

best sense in its context and that of the play as a whole, that it is in

accordance with everything that we know Aeschylus' style, and so is

probably what Aeschylus wrote, then we are justified in saying it. If, however,

we mean that because it is the transmitted text it is

ipso facto preferable to a conjecture that makes better

sense, we are on much shakier ground.

We should ask ourselves what we mean by this. If we are saying

not only that the transmitted text makes sense, but also that it makes the

best sense in its context and that of the play as a whole, that it is in

accordance with everything that we know Aeschylus' style, and so is

probably what Aeschylus wrote, then we are justified in saying it. If, however,

we mean that because it is the transmitted text it is

ipso facto preferable to a conjecture that makes better

sense, we are on much shakier ground.